Labor/Employment,

Government

Jul. 30, 2025

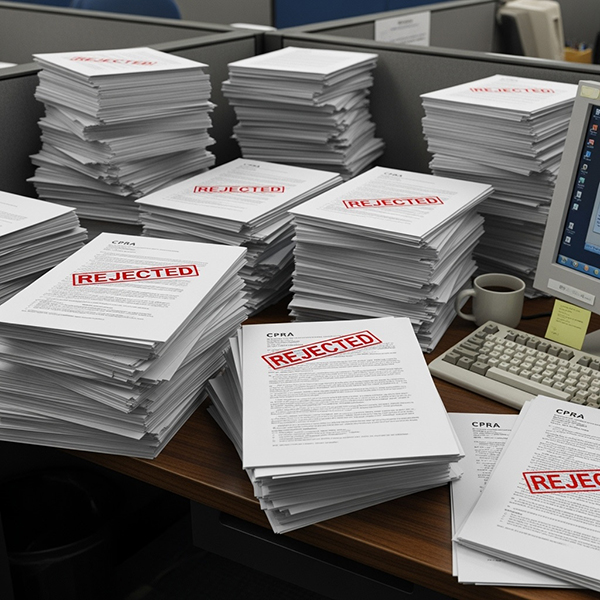

What the California Public Records Act really requires - and what it doesn't

Despite widespread assumptions about quick turnarounds and broad obligations, California's Public Records Act imposes far fewer disclosure requirements than many requesters -- and even some agencies -- commonly believe.

Derek P. Cole

Partner, Co-Founder

Cole Huber LLP

2261 Lava Ridge Ct

Roseville , CA 95661-3034

Fax: (916) 780-9050

Email: dcole@colehuber.com

Derek specializes in municipal and environmental law, providing both advisory and litigation services.

The

California Public Records Act (CPRA) guarantees access to the records of state

and local governments. The act ensures public officials and employees conduct

business transparently. It recognizes that government records belong to -- and

should always be available to -- the people.

But the right to access public records is not unlimited. As

a municipal lawyer, I regularly advise my clients on handling public records

requests. I often encounter misperceptions about what the CPRA requires.

Here's a look at the most common misperceptions -- and what

the act really says.

Fact: Agencies are not required

to produce records within ten days.

The most common misperception is that agencies have ten days

to produce responsive documents.

The CPRA is clear: an agency need only provide a written response

within the 10-day timeframe. (Gov. Code, § 7922.535(a).) The response must

advise whether records exist, whether they will be produced, or whether the

agency claims any exemption from disclosure. (Id., §§ 7922.535(a),

7922.540.) If the agency advises it will produce records, it need only identify

the "estimated" date they will be disclosed. (Id., § 7922.535(a).)

The CPRA provides little guidance on how long an agency may

estimate for its response. It says only that disclosure of records must occur

"promptly" -- a term courts have not interpreted. (Id.,

§ 7922.530(a).)

Requesters and agencies may differ about what is prompt. But

responding to records requests can be like responding to litigation discovery.

My law firm regularly processes several large records productions for our

clients. The volume and complexity of these can rival what our litigators face

in responding to large document demands.

In our experience, it sometimes takes weeks -- and even a few

months -- to respond to requests. Just as in litigation, where discovery

extensions are the norm, requesters should be patient -- especially when they

seek voluminous records.

Fact: The CPRA does not require

agencies to answer questions.

Another misperception is that the CPRA requires agencies to

provide narrative answers to requesters' questions. Often, agencies will

receive CPRA requests that read like interrogatories. Some even demand that agencies

create detailed charts or spreadsheets, complete with instructions on how to

assemble and forward complex data sets.

The CPRA requires agencies only to disclose existing

records. They need not create new records to satisfy requests. (Sander v.

Superior Court (2018) 26 Cal.App.5th 651, 669.)

When our clients receive these requests, we direct them not

to answer the questions or assemble the requested spreadsheets. We advise them only

to provide records that contain the requested information.

Fact: Agencies can ask for

clarification.

Sometimes agencies receive overly broad or vague requests

that preclude any meaningful response. Agencies are not required to do their

best to decipher these.

Examples include requests for entire classes of documents -- such

as "all" documents, notes, or correspondence -- without any reference to

timeframe, context, or authorship. Agencies can only guess about how to fulfill

such requests.

When agencies receive these, they need only make a

"reasonable effort" to have the requesters provide "focused and effective"

requests before proceeding. (Gov. Code, § 7922.600(a), (b).) The agency

may describe "the information technology and physical location" where records

may be found and "provide suggestions for overcoming any practical basis for

denying access to the records or information sought." (Id.,

§ 7922.600(a)(1)-(3).) If agencies are unable to identify responsive

records after this effort, they may advise the requesters accordingly. (Id.,

§ 7922.600(b).)

Fact: Law enforcement reports

are exempt from disclosure.

Law enforcement records are also a source of confusion. A

frequent misperception is that anyone may receive copies of police or sheriff

reports.

California generally exempts "records of complaints to, or investigations

conducted by" law enforcement agencies such as county sheriffs and city police

departments. (Gov. Code, § 7923.600.) Only victims of criminal incidents

(or their representatives) may receive discrete -- and limited -- portions of

such reports, including witness statements, incident details, and property

descriptions. (Id., § 7923.605(a).) But even they may not receive

portions of the reports disclosing the investigating officers' analyses or

conclusions. (Id., § 7923.605(b).)

Law enforcement agencies are, however, required to make

certain information available for criminal incidents. They must release

information about arrestees, bookings, charges, and related matters. (Id.,

§§ 7924.610, 7923.615.)

Fact: Architectural drawings

cannot be copied without permission from copyright holders.

Another misperception concerns architectural drawings.

Agencies must usually withhold building plans, for instance, due to copyright

protections. (Gov. Code, § 7927.705.)

Agencies may, however, make copyrighted plans available for

inspection. (Id., § 65103.5(a).) But without the permission of

the design professional or copyright holder, agencies cannot allow the plans to

be copied. (Id., § 65103.5(b).) Absent permission, even the owners of

the buildings cannot receive copies.

Fact: Template request forms

found online are not helpful.

Finally, a word about the CPRA request templates found

online: in my opinion, these are unhelpful. Many include lengthy discussions of

legal standards and requirements that government employees already know. Some

still refer to the old code numbering system that was replaced in 2023. (If you

see a template citing sections in the 6000s, it is outdated.)

Most agencies provide request forms or portals on their

websites. If this option is available, use it.

Regardless of how a request is submitted, the most important thing is how you describe your requests. The more attention you devote to describing these, the better your chance of success. So be clear about what you want.

Submit your own column for publication to Diana Bosetti

For reprint rights or to order a copy of your photo:

Email

Jeremy_Ellis@dailyjournal.com

for prices.

Direct dial: 213-229-5424

Send a letter to the editor:

Email: letters@dailyjournal.com